blind, visually impaired, or low sighted?

There is an ongoing debate about what to call it. Visual Impairment or blindness? What is correct: A blind person or a person living with blindness or a person with low vision? But what is the right word? Well, I doubt there is just one.

The first thing I learned in my very first interviews was that blindness is highly individual. A lot of sighted people have the preconception that blindness means you have a black curtain in front of your eyes and you can’t see anything. Even if we stick with just the terms for blindness for a bit now, it’s still a lot more complicated than just that!

Legal Blindness is different from total blindness

In Austria, legal blindness is defined by visual acuity in the following cases:

0.02 (1/60) without visual field defects

0.03 (2/60) with quadrantanopsia

0.06 (4/60) with hemianopsia

0.1 (6/60) with tunnel vision

severe visual impairment in comparison:

0.05 (3/60) without visual field defects

0.1 (6/60) with quadrantanopsia

0.3 (6/20) with hemianopsia

1.0 (6/6) with tunnel vision.

This is defined by BPGG §4a. The BPGG stands for Bundes-Pflege-Geld-Gesetz, which approximately translates to the Federal Care Allowance Act. It handles the distribution of disability benefits under the Austrian social system. Of course, the exact definition will vary depending on your country’s social system.

So legal blindness is a convention on visual acuity in combination with field of vision, not a diagnosis itself.

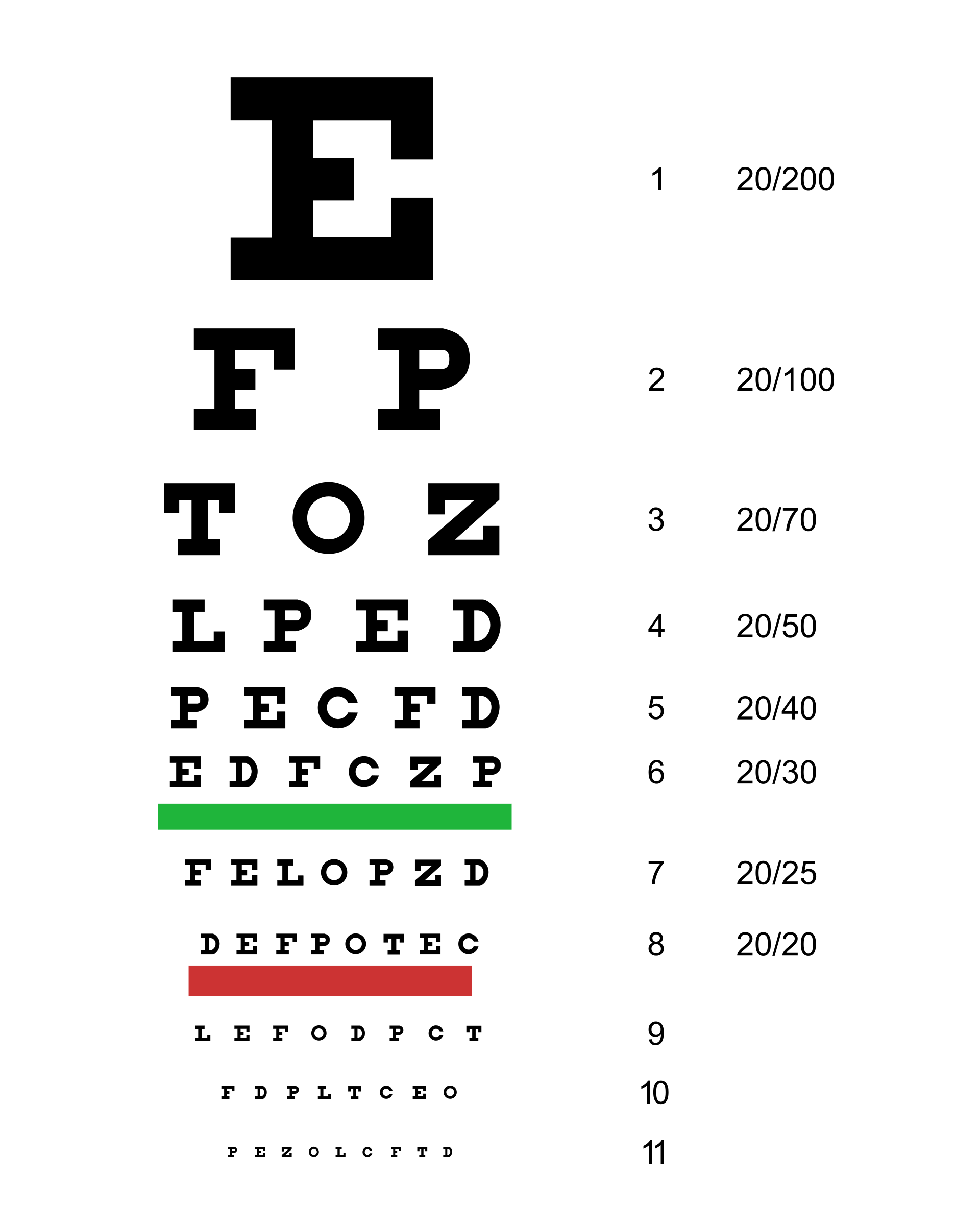

When I am explaining what I do to people outside the accessibility space, I like to give them this as a reference: With the best possible prescription glasses, you would be able to identify only the biggest letter on the top of the eyesight chart.

Snellen Chart By Jeff Dahl - Own work by uploader, Based on the public domain document: [1], CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4262200

Some people can identify contrast, contours, and colors - although color blindness is a whole other beast - some might have cloudy vision or blind spots, or the exact opposite: a very narrow field of vision. There are many different medical conditions that cause visual acuity loss. Some develop gradually, like retinitis pigmentosa, but some can happen out of the blue, like apoplexia papillae. If your Latin is rusty, don’t worry: one is a nerve thing and the other is caused by insufficient blood supply to the optic nerve.

Who prefers what?

My approach to this is to simply ask. Blindness is a highly individual experience. Even with approximations with a percentage of vision, a diagnosis such as 2% can look different depending on the person you ask. I usually start my interview or usability testing process with the same set of baseline questions. These always include something along the lines of “Could you tell us how your vision works?”

Even if I am told in advance that my interview partner has a slight, medium, or strong visual impairment, I still ask that question to level the playing field. Again, blindness is highly individual, I cannot stress this enough! Asking this question can also show how comfortable a person is talking about it, which feeds into one of my underlying interests: societal stigma and self-perception. Once I get the answer to that question, I follow it up with “So how do you want to be referred to?”

It’s as easy as that! And more often than not, the person will also give me the reasoning behind their decision. I love it when that happens because it gives me an insight into how disability is or is not a part of their identity.

At Hope Tech, we are currently using visually impaired because it covers more than strictly blindness, plus it is easy to abbreviate Visually Impaired Person as VIP for internal use. If we know a bit more about our test user, we will adjust accordingly, but VIP is the default for us.

Some people are perfectly fine with being called blind, while others don’t identify as such. I have come to regard it like pronouns. It’s first and foremost a matter of respect to use the correct words that correspond to the person’s identity, even in the protocol that’s meant for internal use only.