DIY Braille Keyboards: The Define Project

Define stands for Digital Equipment For Inclusive Empowerment. The mission behind it is not only to bring low-cost assistive tech to the market but also to improve digital literacy in the process. Braille keyboards aren’t an inherently new idea. But Define takes a hands-on approach to the whole process, and that’s what makes it special in my opinion.

Julia is holding a black version of the Meta Braille keyboard.

User-Led Co-Creation

Over the span of one year, Define has developed a DIY kit to 3D-print a braille keyboard. The print instructions are open source and are free to download from GitHub.

Usually, assembling a keyboard requires soldering contact points. Soldering is not particularly easy or safe for people with low vision to do on their own: It requires a lot of precision and you can’t really check whether everything is connected properly by feeling because you’d run the risk of burning your fingertips off. Yikes!

So the Define Project workshopped a solution to this: Instead of contact points being soldered, they are connected by wrapping wires around them. This ensures steady contact and doesn’t rely on vision, which allows Makers with low to no vision to DIY it on their own.

Through these workshops, a total of 8 MetaBraille keyboards were born. Doesn’t sound like a lot? Well, keep in mind that 3D printing each half of the keyboard shell takes around 4 hours, if the printing process goes smoothly! Because sometimes 3D printers are pranksters and shimmy a bit to the side while printing. The result is a misaligned, unusable print. So if you want to make one yourself, just know it could take a while.

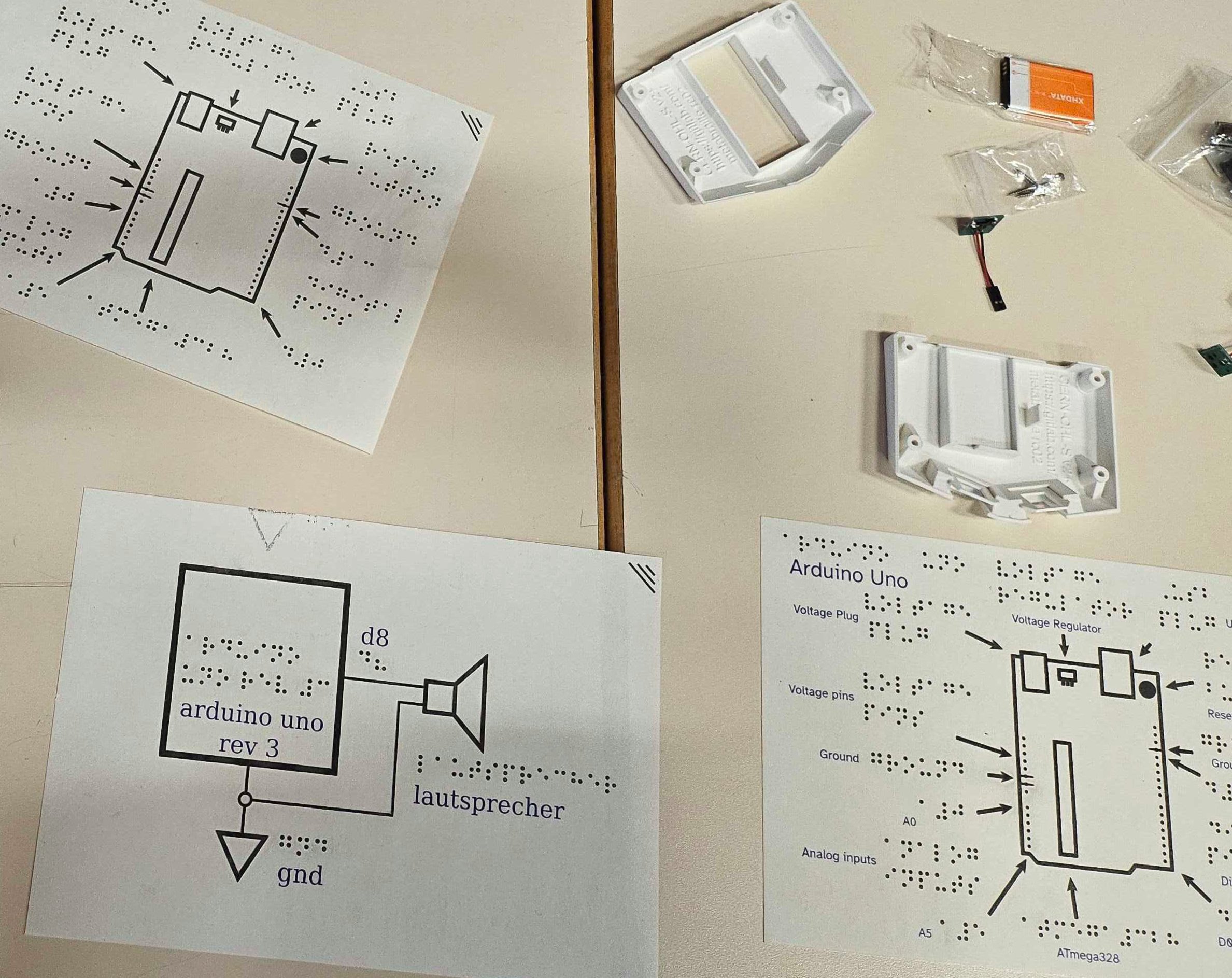

3 plans for the keyboard construction lie on the table. Each one is labeled with English and Braille. In the top right corner is a keyboard shell, battery pack and key-parts. Unfortunately, I lack the technical expertise to explain in detail what exactly we are looking at here. If you have a closer understanding of the matter, please do explain it to me!

How do Braille Keyboards work?

The keyboard is called the MetaBraille. It got its name from the MakerSpace MetaLab in Vienna, where it was born. The top 2 buttons on the keyboard are for navigating, or swiping if you pair it with a smartphone. The 8 buttons on the side facing away from you are for braille input. Of these 8, the 6 black ones are to type letters and the 2 white ones at the bottom are for space and delete. The 2 extra keys also allow for more variety in key combos. They can triple our available key combos for special characters!

How can you type in braille?

Braille is an alphabet where every letter fits on a 2 by 3 grid. You memorize the letters by their dot patterns. Reading braille with your fingers works by identifying the dot pattern as a distinct letter. So for typing, it’s the other way around: You type the dot pattern of a letter by pressing the keys in the corresponding pattern. Learning braille is like memorizing any other alphabet, the letters just take on new shapes!

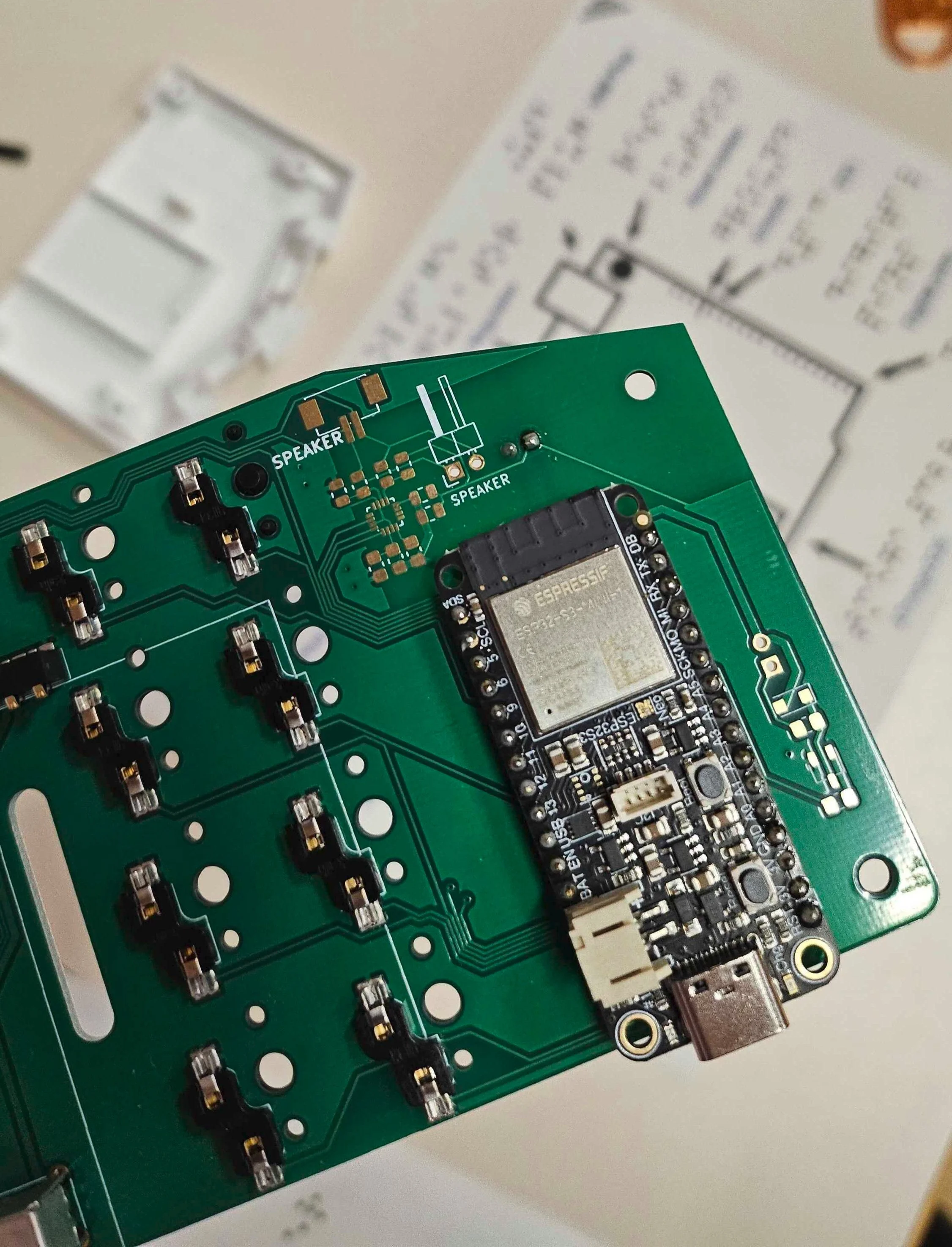

A green circuit board with an ESP32S3 processor on it. This processor is what translates the braille to latin alphabet before transmitting it to the device the keyboard is paired with.

How do they interact with a website?

Virtually like any other keyboard! In the case of the Metabraille, to the device, it will look just like any other Bluetooth keyboard. The translation from braille to the Latin alphabet letters happens within the MetaBraille.

But you know what that means? It’s time to recap the basics of keyboard navigation!

Tab Navigation: The Tab key is used for navigating through interactive elements such as buttons, links, and form fields. The standard stuff. Pressing the Tab key typically moves the focus from one element to the next and Shift+Tab is used to move backwards.

Arrow Keys: You can typically use the arrow keys (up, down, left, right) to move through menus, lists, and other elements.

Enter or Spacebar: These keys are often used to activate or select the currently focused element, like a button or a link. They replace the mouse click or tap with your finger.

Braille keyboards are usually used together with screen reader software. So if you want your website or app to work well with braille keyboards, you also need to check things like alt-texts and HTML tags for sensible heading structures and landmarks, like defining the header, main, and footer as such. Screen readers and keyboard navigation go hand-in-hand (or software-in-hardware?), so learning about one teaches you about the other at the same time. The Mozilla Developer Resources are a great starting point in my opinion, best paired with learning by doing and by that, I mean manually testing out keyboard navigation through your user flow.

Trying out the MetaBraille with some help from the braille tables on the desk. It takes a bit of time to get used to, but it’s surprisingly fast!

In our increasingly digitalized world, it’s initiatives like the Define Project are bridging the digital divide. But no matter how brilliant, no innovation will solve access limitations on its own. It’s still up to all of us to ensure that technology truly serves everyone.